Reviewed by Corey Noles

Apple has just launched something that might surprise you: a formal request system for browser interoperability ideas. This is not another corporate initiative, it is a direct response to mounting regulatory pressure from the EU's Digital Markets Act. The company is now actively seeking input from developers and tech companies about how to make iOS browsers work better with third-party services and devices, a notable shift from its historically closed approach.

The timing says a lot. Apple is proposing a new Web Browser Engine Entitlement that gives browser apps some of the extended privileges any modern, safe browser needs, while the EU has sent preliminary instructions on how it expects the iPhone maker to comply with interoperability provisions. The financial stakes are enormous. Penalties for non-compliance with the DMA can hit up to 10% of global annual turnover, a figure that would represent tens of billions for Apple.

So what does that actually mean for developers, users, and the rest of the tech world?

What is on the table?

The scope of Apple’s interoperability push goes far beyond simple browser tweaks. Device manufacturers and app developers should be able to access nine iOS connectivity features previously kept for Apple’s exclusive use, such as peer-to-peer Wi-Fi connectivity, NFC features, and device pairing. If that happens, non-Apple devices could start playing nicely with iPhones in ways they never have.

Picture the practical stuff. Google could use this opportunity to make AirDrop work with Android devices. Headphone manufacturers could support SharePlay, which only works with AirPods right now. The EU's proposed standards would require Apple to allow third-party devices to run background operations, auto-switch audio, and send and receive files via AirDrop, along with more features when connected to Apple products. That would change daily use, not just edge cases.

Now the browser angle. Apple requires specific iOS APIs for text input, scrolling, dragging, and contextual menus, even though third party browsers already have code for things like scrolling. Apple wants deep system integration, browser vendors already ship their own battle-tested components. Friction is baked in.

This is where competition can suffer. Mandating API adoption may hurt quality and delay release of competing browsers. Vendors face a choice, keep mature cross-platform code or rebuild core functionality with iOS-specific APIs. And even with some new APIs available for web app features, key gaps remain, including the core API for installing and managing Web Apps. Without that, matching Safari on iOS is a reach.

The regulatory pressure is real, and it is working

Apple did not just decide to embrace openness. The company has been designated a "gatekeeper" under the DMA, and the Digital Markets Act aims to restore contestability, interoperability, choice, and fairness in EU digital markets.

Results are already visible. Apple has adopted 6 out of 11 of OWA's recommendations on browser defaults and choice screens. More telling, Apple has fixed 6 important issues that let browsers and Web Apps compete on iOS, including letting EU users uninstall Safari.

One change shows how precise the pressure has become. After Apple's 16 year ban of third-party browser engines, vendors will need phased rollouts and multi-variant testing to introduce their own engines over time. Apple had added a contract rule to explicitly ban that approach. On October the 23rd, the contract was updated to remove that single line. That kind of surgical tweak does not happen without regulators reading the fine print.

The pressure is not easing. The European Commission issued preliminary findings on how Article 6(7) should apply to Apple’s operating system when third parties request access to hardware and software features. The signal is clear, compliance is not optional.

Why Apple’s resistance makes business sense

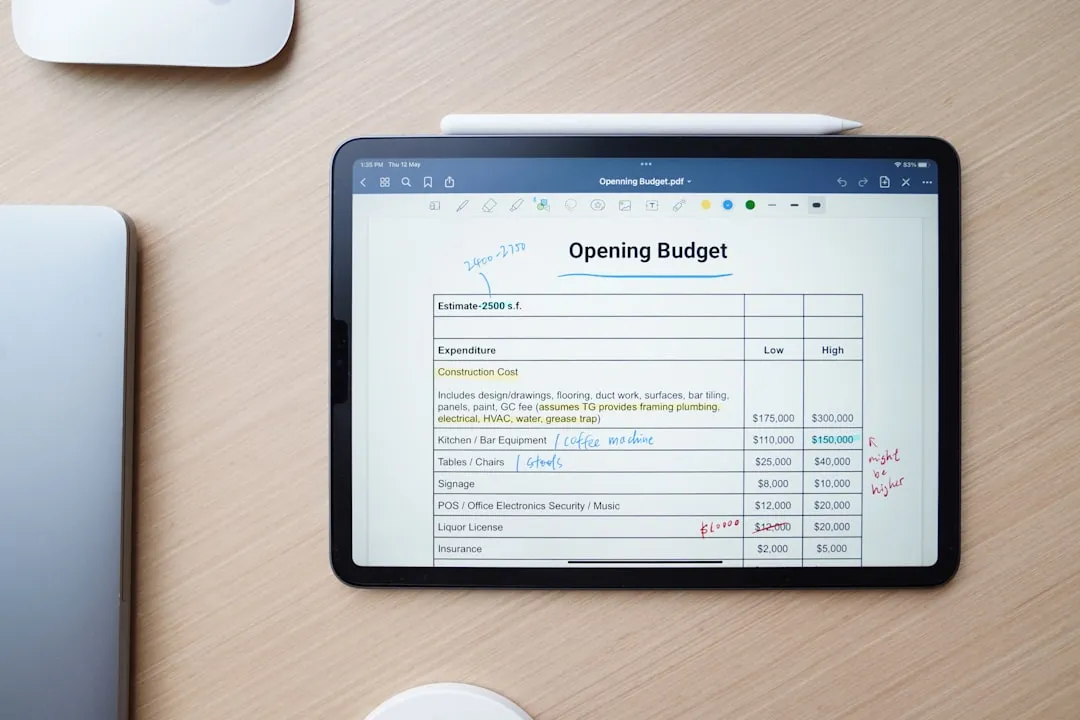

Look at the incentives. Safari is the highest margin product Apple has ever made, accounts for 14 to 16% of annual operating profit, and brings in 20 billion dollars per year in search engine revenue from Google. For every 1% browser market share Safari loses, Apple stands to lose 200 million dollars per year.

Set that 20 billion against total services revenue of 85.2 billion dollars in fiscal 2024, and Safari is nearly a quarter of one of Apple’s fastest growing, most profitable segments. No wonder Apple benefits from higher usage of native apps on iOS due to its App Store revenue model, and why the company maintains that the Web, Web Apps, is an alternative to the App Store.

The technical rules fit those financial incentives. All browsers on iOS must run on Apple's WebKit browser engine, and they are restricted to the same system WebKit version. The WebKit requirement has been in place since the App Store launched in 2008, a 16 year moat around browser dominance that has generated hundreds of billions across App Store and search revenue.

Apple’s legal posture fits the pattern. Apple on Monday began a legal challenge to the European Commission's "unreasonable" demand that it open its platforms to rivals, arguing that these rules will severely limit its ability to deliver innovative products and features to Europe, which would lead to an inferior user experience for European customers.

The core argument is blunt. Apple says it is being forced to hand its innovations to direct competitors at no charge, while those competitors are not required to reciprocate. Hard to swallow if you are Apple, and a reminder that interoperability can reshape competition in ways traditional antitrust did not fully address.

Where do we go from here?

Developers are cautious but hopeful. As one put it, "true choice in browsers is the most important counterbalance to gatekeeper monopoly power." The hard part is execution.

Many developers worry Apple will ring fence access to new browsers, especially for testing. Others question whether browser variability by country of residence is real progress. For web developers, geographic fragmentation makes consistent experiences a moving target.

Testing has been a flash point. Apple initially made it impossible for browser vendors to test their own browsers if developers were not physically in the EU. Apple has since addressed that obstacle. Even so, it showed how compliance steps can add new barriers while removing old ones.

PRO TIP: If you are a developer working on browser compatibility, keep a close eye on Apple’s interoperability portal submissions. The requests being made, and Apple’s responses, will signal which iOS restrictions might loosen next and help you plan priorities.

One thing is becoming clear. The current technical and contractual barriers make meaningful browser engine competition effectively impossible, despite Apple’s claims to the contrary. The key issue is that Apple's rules and technical restrictions are blocking other browser vendors from successfully offering their own engines to users in the EU. Until Apple lifts these barriers, it is not in effective compliance with the DMA.

The path forward requires more than cosmetic compliance. Apple could allow browsers to ship two separate versions, one for the EU and one for the rest of the world, so vendors can transition EU users gradually without losing their existing base. That single change would remove a critical blocker for major vendors considering iOS with their own engines.

The stakes are bigger than browser choice. This is about the future of open web standards and real competition in mobile ecosystems. Apple’s interoperability portal could be a step toward openness, or elaborate compliance theater designed to preserve advantages while appearing to play ball.

Given how much Safari contributes to services revenue and operating profit, Apple has every incentive to protect that stream with careful compliance that leaves practical barriers standing. The real test is whether actual browser choice materializes on iOS in the coming months, not a hollow choice trapped inside ecosystem constraints but genuine alternatives that offer meaningfully different browsing experiences.

If I had to bet, we will see progress, then pushback, then more progress. The ball is in Apple’s court.

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!